Uluru (Ayers Rock) with Kata Tjuta (The Olgas) in the distance, Australia (Enlarge)

Throughout the ages many cultures have conceived of geographic space and expressed those conceptions in a variety of ways. One expression of these conceptions has been the establishment of sacred geographies. Sacred geography may be broadly defined as the regional (and even global) geographic locating of sacred places according to various mythological, symbolic, astrological, geodesical, and shamanic factors.

Perhaps the oldest form of sacred geography, and one that has its genesis in mythology, is that of the aborigines of Australia. According to Aboriginal legends, in the mythic period of the beginning of the world known as Alcheringa - the Dreamtime - ancestral beings in the form of totemic animals and humans emerged from the interior of the Earth and began to wander over the land. As these Dreamtime ancestors roamed the Earth they created features of the landscape through such everyday actions as birth, play, singing, fishing, hunting, marriage, and death. At the end of the Dreamtime, these features hardened into stone, and the bodies of the ancestors turned into hills, boulders, caves, lakes, and other distinctive landforms. These places, such as Uluru (Ayers Rock) and Kata Tjuta (the Olgas Mountains) became sacred sites. The paths the totemic ancestors had trod across the landscape became known as Dreaming Tracks, or Songlines, and they connected the sacred places of power. The mythological wanderings of the ancestors thus gave to the aborigines a sacred geography, a pilgrimage tradition, and a nomadic way of life. For more than forty thousand years - making it the oldest continuing culture in the world - the Aborigines followed the Dreaming tracks of their ancestors.

During the course of the yearly cycle various Aboriginal tribes would make journeys, called walkabouts, along the songlines of various totemic spirits, returning year after year to the same traditional routes. As people trod these ancient pilgrimage routes they sang songs that told the myths of the Dreamtime and gave travel directions across the vast deserts to other sacred places along the songlines. At the totemic sacred sites, where dwelt the mythical beings of the Dreamtime, the aborigines performed various rituals to invoke the kurunba, or spirit power of the place. This power could be used for the benefit of the tribe, the totemic spirits of the tribe, and the health of the surrounding lands. For the aborigines, walkabouts along the songlines of their sacred geography were a way to support and regenerate the spirits of the living Earth, and also a way to experience a living memory of their ancestral Dreamtime heritage.

Uluru, Australia (Enlarge)

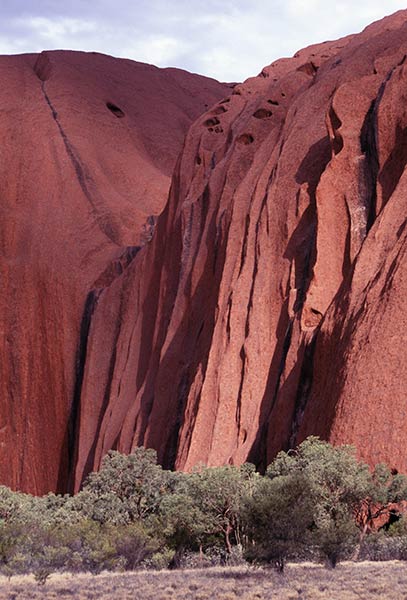

Located in the center of Australia, the massive rock formations of Uluru (Ayers Rock) and Kata Tjuta (the Olgas) are the most prominent and well known sacred sites of the Aboriginal people. Rising 346 meters high, with a circumference of 9.4 kilometers and covering an area of 3.33 square kilometers, Uluru is the single largest rock outcropping all of Australia. Uluru is often referred to as a monolith, and for many years was listed in record books as the world’s largest monolith. That description, however, is inaccurate, as Uluru is part of a much larger underground rock formation which includes Kata Tjuta. The world’s largest monolith is actually Burringurrah (Mt Augustus) in Western Australia, which is more than 2.5 times the size of Uluru, stands 858 metres above the ground and covers and area of 48 square kilometers. In various tourist guidebooks it is said that 2/3 of Ayers Rock is beneath the surrounding land but this is not the case according to the science of geology, which explains that Uluru is only the exposed tip of a much greater mass of rock extending far below the surrounding plain as an integral part of the earth’s crust. Separated from one another by approximately 50 kilometers, Uluru and Kata Tjuta are situated along a straight line passing onto another holy peak known as Mount Conner.

Geologists disagree about the origins of Uluru and Kata Tjuta. The most widely held theory is that both rocks are the remnants of a vast sedimentary bed laid down some 600 million years ago. Over eons of time the bed was raised and folded by movements of the earth’s crust, formed into a mountain range, and then slowly eroded leaving the towering rocks behind. The sandstone rock of Uluru is actually gray but is covered with a distinctive red iron oxide coating, while the thirty-six domes of Kata Tjuta are a harder type of granite composed of quartz and feldspar. The origins of the cave-like depressions on both outcroppings, especially those of Uluru, are the subject of debate among geologists but the most commonly held view is that the rock surfaces had been partly eroded and enlarged to form the depressions.

The beginning of Aboriginal settlement in the Uluru region has not been determined, but archaeological findings to the east and west indicate a date more than 10,000 years ago, though some scholars estimate that human settlement in the region may actually date to 22,000 years ago. According to Aboriginal myths, Uluru and Kata Tjuta provide physical evidence of feats performed during the Dreamtime creation period. The aboriginal tribe of Anangu are the direct descendants of these beings and are responsible for the protection and appropriate management of these ancestral lands. The knowledge necessary to fulfill these responsibilities has been passed down from generation to generation. To the Pitjantjatjara, Yankunytjatjara and Anangu tribes Uluru represents the living core of their belief. No other place in Australia is so rich in mythology, song-lines and stories, or so associated with events from the Alcheringa or Dreaming. In the language of the local Aborigines. ‘Uluru' is simply a local family name that is applied to both the rock and the waterhole on top of the rock. The thirty-six rounded rocks of Kata Tjuta (meaning ‘Many Headed Mountain’), are located in the same National Park as Uluru and the tallest rock, Mt. Olga at 546 meters is about 200 meters higher than Uluru. Kata Tjuta is much less visited by tourists that Uluru and therefore has a more peaceful feeling.

Uluru, Australia (Enlarge)

By Aboriginal tradition only certain elderly males may climb the rock but despite this tradition the Australian government allows tourists to make the climb using a metal chain installed in 1964. Over the years there have been at least forty deaths, mainly due to heart failure while climbing Uluru, and several people have plumetted to their death while climbing. The Anangu tribe also request that visitors do not photograph certain sections of Uluru, mostly gender-related sacred places, for reasons related to traditional beliefs. This photographic ban is intended to prevent Anangu Aborigines from inadvertently violating this taboo by encountering photographs of the forbidden sites.

The first sighting of Kata Tjuta by a European was in July of 1872, when Ernest Giles was exploring the country some 100 kilometers to the northeast. Giles progress towards Kata Tjuta was barred by a large lake. He later named the lake and the Kata Tjuta rocks after the then King and Queen of Spain: Amadeus and Olga. Giles returned to explore the area again in 1873 but was beaten to Uluru by William Gosse who sighted the monolith on July 19 and named it after the Chief Secretary of South Australia, Sir Henry Ayers. Giles also was the first European to climb the rock which he did accompanied by an Afghan camel driver.

The inhospitable nature of the terrain ensured that few whites were to venture into the region. Farmers were defeated by the lack of water and the only whites to pass through the area were trappers, miners and the occasional missionary. The area was declared an Aboriginal Reserve in 1920 and this existed until the 1940s when road access, the possibility of gold in the area, and the tourist potential of Uluru, showed how fragile the original reserve had been. Ayers Rock was created a national park in 1950 and in 1958 was combined with the Olgas to form the Ayers Rock National Park. In 1959 a motel lease was granted near the rock and soon after an airstrip was built. By the 1970s, Ayers Rock and Mount Olga had become the most famous stop on the outback tourist circuit. In 1976 the Commonwealth Government set up the lease at Yulara (a resort complex and service village located 20 km from the base of Uluru) and in 1983 the old tourist facilities near the rock were closed down. In 1985 the title to Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park was returned to the local Pitjantjatjara Aborigines who, in turn, granted the Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service a 99 year lease on the park. Today the Park is jointly managed under direction of a Board of Management that includes a majority of Anangu traditional owners. The Aboriginal community of Mutitjulu is near the western end of Uluru. In 1995, in acknowledgement of Anangu ownership and their relationship with the area, the name of the park was changed from Ayers Rock-Mount Olga to Uluru-Kata Tjuta, its traditional name. Uluru is listed as a World Heritage Area for its natural and man-made attributes.

Bibliography

Breeden, Stanley; Uluru: Looking after Uluru-Kata Tjuta - The Anangu Way. Simon & Schuster Australia, East Roseville, Sydney. Reprint: 2000.

Chatwin, Bruce; The Songlines; Penguin Books; London; 1988

Cowan, James & Colin Beard; Sacred Places in Australia; Simon & Schuster Australia; East Roseville; 1991

Hill, Barry; The Rock: Travelling to Uluru. Allen & Unwin; Sydney

Mountford, Charles P.; Ayers Rock: Its People, Their Beliefs and Their Art. Angus & Robertson. Amended reprint: Seal Books, 1977

Baker, L; Minkiri: A Natural History of Uluru by the Mutitjulu Community, IAD Press; Alice Springs; 1996

Breeden, S.; Uluru: Looking After Uluru-Kata Tjuta the Anangu Way; Simon and Shuster; Sydney; 1994

Layton, R.; Uluru: An Aboriginal History of Ayers Rock; Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies; Canberra; 1986

Wilson, Colin; The Atlas of Holy Places & Sacred Sites; DK Publishing; London; 1996

Tacon, Paul S.C.; Identifying Ancient Sacred Landscapes in Australia: From Physical to Social; Archaeologies of Landscape, Ashmore, Wendy (ed.)

Aboriginal mythology

http://www.ourpacificocean.com/australia_aboriginal_mythology/index1.htm

Martin Gray is a cultural anthropologist, writer and photographer specializing in the study of pilgrimage traditions and sacred sites around the world. During a 40 year period he has visited more than 2000 pilgrimage places in 165 countries. The World Pilgrimage Guide at sacredsites.com is the most comprehensive source of information on this subject.

Martin Gray is a cultural anthropologist, writer and photographer specializing in the study of pilgrimage traditions and sacred sites around the world. During a 40 year period he has visited more than 2000 pilgrimage places in 165 countries. The World Pilgrimage Guide at sacredsites.com is the most comprehensive source of information on this subject.