The twelve Shia Imams, on a pilgrims banner, Karbala, Iraq (Enlarge)

The existence of pilgrimage places, other than the holy shrine of the Ka'ba in Mecca, is a controversial subject in Islam. Sunni Muslims, following the dictates of Muhammad's revelations in the Koran, assert that there can be no pilgrimage site besides Mecca. When Muhammad died, he was buried in the house of his wife Aisha and it was forbidden to visit his grave. In accordance with his teachings, no special treatment was given to the burial places of the four Rightly Guided Caliphs and shrines were not erected over any of their graves. Likewise, Sunni's maintain that the belief in and visits to the graves of saints is not Koranic. The reality, however, is that saints and pilgrimage places are extremely popular throughout the Islamic world, particularly in Morocco, Tunisia, Pakistan, Iraq and Iran.

To understand the practice of pilgrimage in Iran it is first necessary to know something about the differences between the two major sects of Islam, Sunni and Shi'ite, in particular why and when those differences historically arose. Prior to his death, Muhammad had not stated with absolute clarity who should carry on with the leadership of the new religion of Islam. He had no surviving sons and had not even indicated what type of leadership should replace him. Muhammad's death on June 8, 632, therefore thrust the community of believers into a debate over the criteria of legitimate succession. According to sources compiled two to three centuries after Muhammad's death, two primary solutions to the problem of succession arose. One group maintained that the Prophet had designated his cousin and son-in-law Ali (Alī ibn Abī Ṭālib) to be his successor. The other group, convinced that Muhammad had given no such indication and that his speeches which had referred to Ali as his successor were misinterpreted by Shias, chose from among their group the elder disciple, Abu Bakr, who had been the Prophet's first adult male convert and was the father of his wife Aisha. The process of choosing the successor was itself undemocratic because Ali and his supporters were not present at the meeting, being occupied with the burial of Muhammad. Those who supported Abu Bakr were in the majority and formed the nucleus of what later became the 'people of the Sunna and the Assembly', Sunnis for short. The group that supported Ali was called the Shi'a (meaning 'party' or 'supporters' of the house of Ali), later popularly known as the Shi'ite.

Abu Bakr, who ruled for appriximately two years and three months, was followed in turn by the caliphs Umar and then Uthman, upon whose death the caliphate finally passed to Ali. According to the Shi'ites, the first three caliphs who ruled for twenty-four years, are considered usurpers for having deprived Ali of his right to rule. After Ali became Caliph in 656, he was unable to overcome the opposition of his rivals and was assassinated in 661. Ali's supporters maintained that Ali's elder son, Hasan, should become the next caliph but he was prevented from doing so by Muawiya (a cousin of the earlier Caliph Uthman) who usurped the caliphate. Ali's second son, Hussain, under great pressure from Muawiya, agreed to postpone his claim for the caliphate until the death of Muawiya, but was prevented from achieving this aim by the further treachery of Muawiya, who designated his own son Yazid as caliph. The Shi'ites, refusing to accept Yazid as caliph, revolted and their leader Hussain (Ali's second son and the third Imam) was killed in the battle of Karbala in 680 AD. Ever since the caliphate passed to Muawiya and the hereditary dynasty of the Umayyads (later followed by their foes the Abbasids), the Shi'ites have agitated to replace what they consider to be usurpers with a true descendant of the Prophet Muhammad.

The distinctive institution of Shia Islam as practiced in Iran (for there are several different forms of Shia in the Islamic world) is the Imamate, which states that there were twelve Imams as Mohammad's successors. A primary dogma of the Imamate is that the successor of Muhammad, besides being a political leader, must also be a spiritual leader with the ability to interpret the inner mysteries of the Koran and the Sharia (sacred law of Islam). The Shi'ites maintain that the only legitimate heir and successor of Mohammad is Ali, both by right of birth and by the will of the Prophet. Shias revere Ali as the First Imam, and his descendants, beginning with his sons Hasan and Hussain, continue the line of the Imams until the Twelfth, who is believed to have ascended into a supernatural state to return to earth before judgment day. In Shia Islam the term Imam is traditionally used only for Ali and his eleven descendants, while in Sunni Islam an imam is simply the leader of congregational prayer. (The Shia doctrine of the Imamate was not fully elaborated until the tenth century. Other dogmas developed still later. A characteristic of Shia Islam is the continual exposition and reinterpretation of doctrine.) While none of the Twelve Shia Imams, with the exception of Ali, ever ruled an Islamic government, their followers always hoped that they would assume the leadership of the Islamic community. Because the Sunni caliphs were aware of this hope, the Shia Imams were generally persecuted throughout the Umayyad and Abbasid dynasties. The matter of this persecution, beginning with Ali and his sons and continuing with the succeeding eight Imams, is crucial to understanding the motivations and practices of Shia pilgrimage in Iran and Iraq.

Although Shias have lived in Iran since the earliest days of Islam, and there was a Shia dynasty in a region of Iran during the 10th and 11th centuries, it is believed that most Iranians were Sunnis until the 17th century. The Safavid dynasty made Shia Islam the official state religion in the 16th century and aggressively proselytized on its behalf. It is also believed that by the mid-seventeenth century most people in what is now called Iran had become Shias, an affiliation that has continued.

A significant and highly visible practice of Shia Islam is that of visiting the shrines of the Imams in Iraq and in Iran. It is interesting to note that only one of the Imam shrines is located in Iran, that of Imam Reza in Mashhad, while the other Imams' shrines are found in Iraq and Saudi Arabia. This curious matter is historically explained by the fact the reigning caliphs of the Umayyad and Abbasid dynasties were concerned that the Shi'ite Imams might mobilize their followers and seek either the overthrow of the Sunni leadership or attempt to set up a rival caliphate in another part of the Islamic world. As a result, many of the Shi'ite Imams were kept under house arrest in Iraq and, according to Shi'ite beliefs, many of them were assassinated, mostly by poison. From the 10th century onward, the mausoleums of the Shi'ite Imams in both Iraq and Iran have become locations highly visited by the various Shia sects because of the difficulty and expense of making the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca. Shia believers, following the dictates of Muhammad, will seek to visit Mecca at least once during their lifetimes but pilgrimages to the shrines of the Imams are generally far more popular. Again, while Sunni considers the veneration of saints and Imams (and pilgrimages to their shrines) to be heretical, followers of the Shi'ite sects rationalize their pilgrimage practices by recourse to a particular passage in the Koran. Sura 42:23 (I do not ask of you any reward for it but love for my near relatives) is interpreted by the Shi'ites as expressing Muhammad's permission that the shrines of his relatives should be respected, maintained and visited. The Shi'ite shrines in Sunni Iraq have frequently been destroyed or desecrated by fanatic Sunnis but each time the shrines are reconstructed, ever more gloriously, by Shi'ite believers.

The shrine locations of the twelve Shi'ite Imams are:

- Ali ibn Abi Talib; in Najaf, Iraq

- al-Hasan (Alhasan); in Medina, Saudi Arabia

- al-Hussain (Alhussain); in Karbala, Iraq

- Ali Zayn al-Abidin (Alabideen); in Medina, Saudi Arabia

- Muhammad al-Baqir (Albaqir); in Medina, Saudi Arabia

- Jafar al-Sadiq (Alsadiq); in Medina, Saudi Arabia

- Musa al-Kazim (Alkadhim), in Baghdad, Iraq

- Ali al-Rida (Reza, Alridha); in Mashhad, Iran

- Muhammad al-Jawwad (Aljawad); in Baghdad, Iraq

- Ali al-Hadi (Alhadi); in Samarra, Iraq

- Hassan al-Askari (Alhasan Alaskari); in Samarra, Iraq

- Muhammad al-Mahdi (Almahdi); the Hidden Imam

Tile Work, Iran (Enlarge)

Besides the highly visited shrines of the Imams, there are two other categories of Islamic pilgrimage sites in Iran. These are imamzadihs, or the tombs of descendants, relatives and disciples of the twelve Imams; and the mausoleums of revered Sufi saints and scholars (Sufism being the esoteric or mystical tradition of Islam). After the 9th century the veneration of the tombs of pious men (and sometimes women) became extremely popular, especially in eastern Iran, and the memorial tomb, often with an accompanying religious school, assumed a leading place among the types of monumental buildings in Persian architecture. However, the practice of erecting tombs owed nothing to Koranic dogma but instead rested on deep-seated popular beliefs and the near-universal Iranian tendency to venerate and continuously mourn the martyred Imams. Other types of pilgrimage places exist in Iran, including sacred trees, wells and footprints, but these too are identified with particular holy persons who may have visited or in some other way been associated with the place.

The word imamzadih is used to refer both to a shrine where a descendant of an Imam is buried and also to the actual descendant. Thus, when visiting a shrine, a pilgrim (za'ir in Persian) is also paying a personal visit to a revered individual. The grave of a saint (awliya) is a point of psychic contact with the saint for the tomb is conceived as the dwelling place of the saint and may be compared in function to the Christian martyrium. Saints, Imams and the individuals enshrined in the Imamzadihs are viewed as having a close relationship with God and are therefore approached by pilgrims as intercessors. Pilgrims visit the shrine of a saint in order to receive some of his spiritual power (baraka) and making a pilgrimage (ziyarat) also brings the pilgrim religious blessing.

Writing of pilgrimage In Iran, the anthropologist Anne Betteridge explains, "Shi'I Muslim shrines are referred to as thresholds. The most important shrine in the country, site of the eighth Imam's tomb in Mashhad, is formally entitled "Astan-e Qods-e Razavi" - 'the threshold of holiness of Riza'. On such thresholds conventional relations of cause and effect are suspended: supernatural powers may be brought to bear on problems that do not yield to conventional forms of redress or where conventional means are not within the reach of troubled individuals. Pilgrimage is performed with tangible purposes in mind. Pilgrims visit shrines in the hopes that they will be the beneficiaries of divine favor in some palpable way, but they comment that the experience of pilgrimage is comforting and heart-opening in and of itself. Time and again I met people who, when distraught and unable to discuss problems with relatives and friends, would visit imamzadihs to find calm and comfort.Imamzadihs, by virtue of their association with the Imams, are thought able to work miracles - events that cannot be caused by human abilities or natural agency. The Imams and their descendants are approached as individuals; they are contacted as men and women who have experienced difficulties similar to those that plague pilgrims at the shrines. As a result of their own experience of tragedy, saints may be both sympathetic and helpful. The saints' individuality is reflected in their miraculous specializations.Certain shrines in Shiraz are perceived as having specialties in miraculous action. As a result, each pilgrim in search of divine assistance is presented with an array of shrines and saints to be consulted, depending upon how he or she defines the problem at hand. Through declaration of a vow, a believer attempts to forge an alliance with an Imam or imamzadih and to state his or her case in such a way that it will compel a favorable response. If a favor is granted, the officially recognized correspondence between the holy personage and the believer may be celebrated publicly at the relevant shrine."

For further information on pilgrimage in the Shi'ite tradition, particularly in the city of Shiraz, consult chapter ten (Specialists in Miraculous Action: Some Shrines in Shiraz, by Anne Betteridge) in Sacred Journeys: The Anthropology of Pilgrimage; edited by Alan Morinis.

Additional notes on Shia Islam: (Information Courtesy: The Library of Congress - Country Studies)

All Shia Muslims believe there are seven pillars of faith, which detail the acts necessary to demonstrate and reinforce faith. The first five of these pillars are shared with Sunni Muslims. They are shahada, or the confession of faith; namaz, or ritualized prayer; zakat, or almsgiving; sawm, fasting and contemplation during daylight hours during the lunar month of Ramazan; and hajj, or pilgrimage to the holy cities of Mecca and Medina once in a lifetime if financially feasible. The other two pillars, which are not shared with Sunnis, are jihad--or crusade to protect Islamic lands, beliefs, and institutions, and the requirement to do good works and to avoid all evil thoughts, words, and deeds.

Twelver Shia Muslims also believe in five basic principles of faith: there is one God, who is a unitary divine being in contrast to the trinitarian being of Christians; the Prophet Muhammad is the last of a line of prophets beginning with Abraham and including Moses and Jesus, and he was chosen by God to present His message to mankind; there is a resurrection of the body and soul on the last or judgment day; divine justice will reward or punish believers based on actions undertaken through their own free will; and Twelve Imams were successors to Muhammad. The first three of these beliefs are also shared by non- Twelver Shias and Sunni Muslims.

The Twelfth Imam is believed to have been only five years old when the Imamate descended upon him in A.D. 874 at the death of his father. The Twelfth Imam is usually known by his titles of Imam-e Asr (the Imam of the Age) and Sahib az Zaman (the Lord of Time). Because his followers feared he might be assassinated, the Twelfth Imam was hidden from public view and was seen only by a few of his closest deputies. Sunnis claim that he never existed or that he died while still a child. Shias believe that the Twelfth Imam remained on earth, but hidden from the public, for about seventy years, a period they refer to as the lesser occultation (gheybat-e sughra). Shias also believe that the Twelfth Imam has never died, but disappeared from earth in about A.D. 939. Since that time the greater occultation (gheybat-e kubra) of the Twelfth Imam has been in force and will last until God commands the Twelfth Imam to manifest himself on earth again as the Mahdi, or Messiah. Shias believe that during the greater occultation of the Twelfth Imam he is spiritually present--some believe that he is materially present as well-- and he is besought to reappear in various invocations and prayers. His name is mentioned in wedding invitations, and his birthday is one of the most jubilant of all Shia religious observances.

Like Sunni Islam, Shia Islam has developed several sects. The most important of these is the Twelver, or Ithna-Ashari, sect, which predominates in the Shia world generally. Not all Shia became Twelvers, however. In the eighth century, a dispute arose over who should lead the Shia community after the death of the Sixth Imam, Jaafar ibn Muhammad (also known as Jaafar as Sadiq). The group that eventually became the Twelvers followed the teaching of Musa al Kazim; another group followed the teachings of Musa's brother, Ismail, and were called Ismailis. Ismailis are also referred to as Seveners because they broke off from the Shia community over a disagreement concerning the Seventh Imam. Ismailis do not believe that any of their Imams have disappeared from the world in order to return later. Rather, they have followed a continuous line of leaders represented in early 1993 by Karim al Husayni Agha Khan IV, an active figure in international humanitarian efforts. The Twelver Shia and the Ismailis also have their own legal schools.

Also consult:

Non-Hajj Pilgrimage in Islam: A Neglected Dimension of Religious Circulation; Bhardwaj, Surinder M.; Journal of Cultural Geography, vol. 17:2, Spring/Summer 1998

Sufism: Its Saints and Shrines: An Introduction to the Study of Sufism with Special Reference to India; Subhan, John A.; Samuel Weiser Publisher; New York; 1970.

Detail of intricate tile work on mosque dome, Yazd (Enlarge)

Tile Work, Iran (Enlarge)

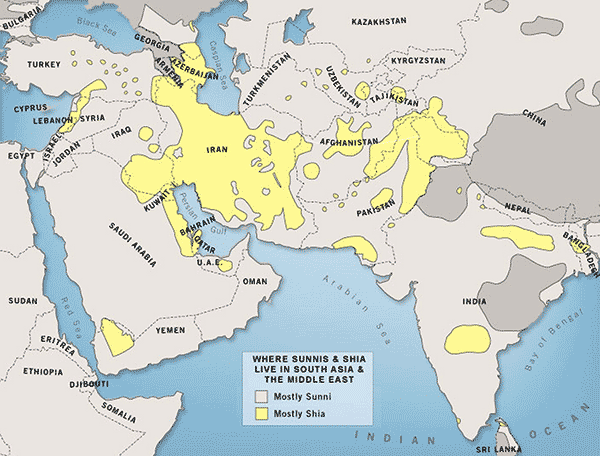

Sunni / Shia Distribution in the Middle East

For additional information:

Martin Gray is a cultural anthropologist, writer and photographer specializing in the study of pilgrimage traditions and sacred sites around the world. During a 40 year period he has visited more than 2000 pilgrimage places in 165 countries. The World Pilgrimage Guide at sacredsites.com is the most comprehensive source of information on this subject.

Martin Gray is a cultural anthropologist, writer and photographer specializing in the study of pilgrimage traditions and sacred sites around the world. During a 40 year period he has visited more than 2000 pilgrimage places in 165 countries. The World Pilgrimage Guide at sacredsites.com is the most comprehensive source of information on this subject.