The Mosque of Djenne, Mali (Enlarge)

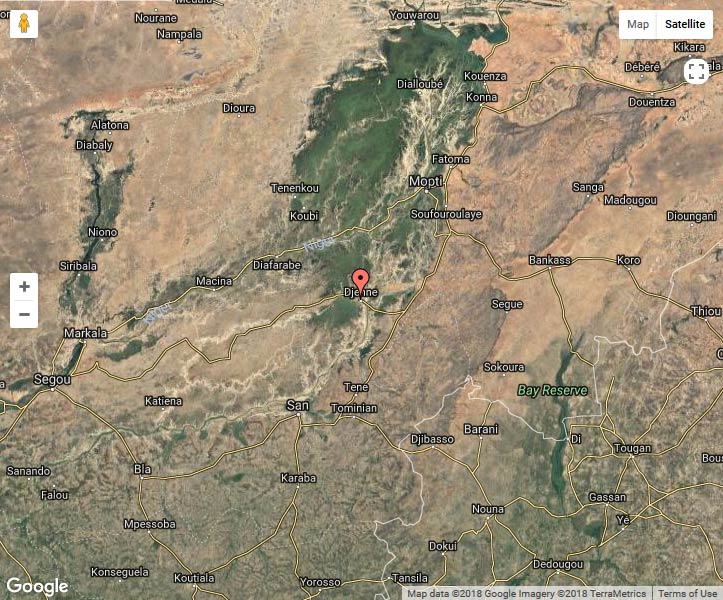

Djenné, the oldest known city in sub-Saharan Africa is situated on the floodlands of the Niger and Bani rivers, 354 kilometers (220 miles) southwest of Timbuktu. Founded by merchants around 800 AD (near the site of an older city dating from 250 BC), Djenné flourished as a meeting place for traders from the deserts of Sudan and the tropical forests of Guinea. Captured by the Songhai emperor Sonni 'Ali in 1468, it developed into Mali's most important trading center during the 16th century. The city thrived because of its direct connection by river with Timbuktu and from its situation at the head of trade routes leading to gold and salt mines. Between 1591 and 1780, Djenné was controlled by Moroccan kings and during these years its markets further expanded, featuring products from throughout the vast regions of North and Central Africa. In 1861 the city was conquered by the Tukulor emperor al-Hajj 'Umar and was then occupied by the French in 1893. Thereafter, its commercial functions were taken over by the town of Mopti, which is situated at the confluence of the Niger and Bani rivers, 90 kilometers to the northeast. Djenné is now an agricultural trade center, of diminished importance, with several beautiful examples of Muslim architecture, including its Great Mosque.

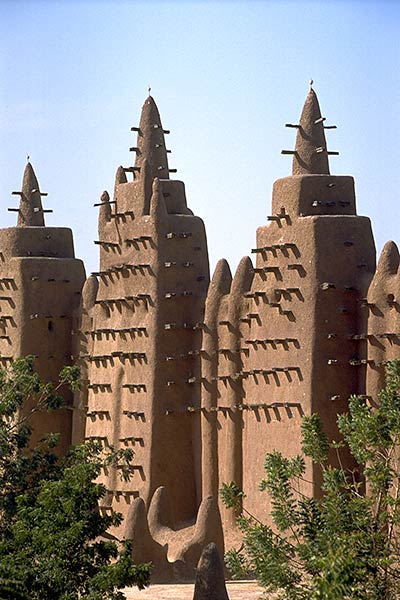

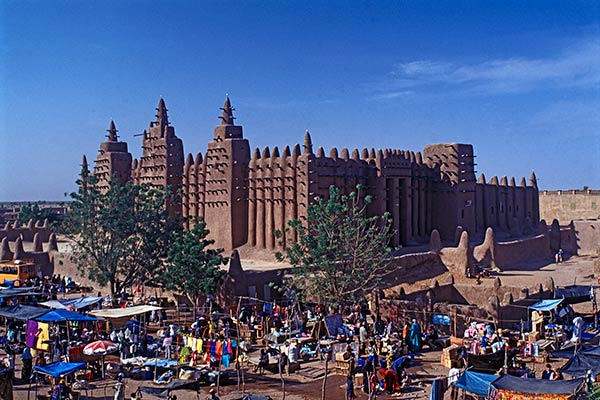

In addition to its commercial importance, Djenné, was also known as a center of Islamic learning and pilgrimage, attracting students and pilgrims from all over West Africa. Its Great Mosque dominates the large market square of Djenné. Tradition has it that the first mosque was built in 1240 by the sultan Koi Kunboro, who converted to Islam and turned his palace into a mosque. Very little is known about the appearance of the first mosque, but it was considered too sumptuous by Sheikh Amadou, the ruler of Djenné in the early nineteenth century. The Sheikh built a second mosque in the 1830's and allowed the first one to fall into disrepair. The present mosque, begun in 1906 and completed in 1907, was designed by the architect Ismaila Traoré, head of Djenné's guild of masons. At the time, Mali was controlled by the French, who may have offered some financial and political support for the construction of the mosque and a nearby religious school.

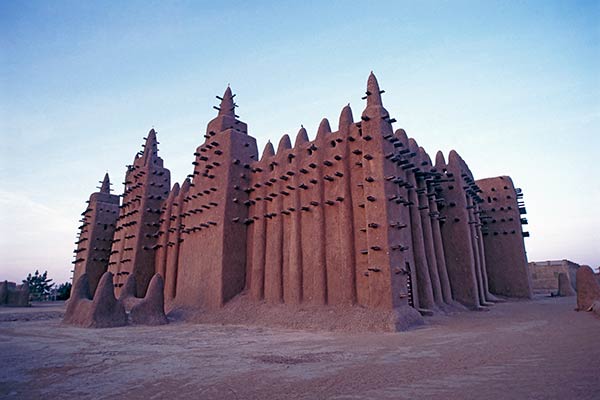

The Great Mosque is built on a raised plinth platform of rectangular sun-dried mud bricks that are held together by mud mortar and plastered over with mud. The walls vary in thickness between sixteen and twenty-four inches, depending upon their height. These massive walls are necessary in order to bear the weight of the tall structure and also provide insulation from the sun's heat. During the day, the walls gradually warm up from the outside; at night, they cool down again. The mosque’s prayer hall, with ninety wooden pillars supporting its ceiling, can contain as many as 3000 people. This helps the interior of the mosque to stay cool all day long. The Great Mosque also has roof vents with ceramic caps. These caps, made by the town's women, can be removed at night to ventilate the interior spaces.

Mud mosque of Djenne (Enlarge)

Djenné's masons have integrated palm wood scaffolding into the building's construction, not as beams, but as supports for the workers who apply plaster during the annual spring festival to restore the mosque. In addition, the palm beams minimize the stress that comes from the extreme temperature and humidity changes that take place during the year. The facade of the mosque has the same structure and building materials as a traditional house in Djenné and includes three massive towers, each topped with a spire capped by an ostrich egg (these ostrich eggs symbolize fertility and purity).

Although the Great Mosque incorporates architectural elements found in mosques throughout the Islamic world, it reflects the aesthetics and materials used for centuries by the people of Djenné. Its use of local materials, such as mud and palm wood, its incorporation of traditional architectural styles, and its adaptation to the hot climate of West Africa are expressions of its elegant connection to the local environment. Such earthen architecture, which is found throughout Mali, can last for centuries if regularly maintained.

The repair or maintenance of the Great Mosque is supervised by a guild of 80 senior masons, who also coordinate the annual spring replastering. Many of the citizens of Djenné work to prepare banco (mud mixed with rice husks) for the event. It may be compared to a community fair "with much festivity and laughter," as described by a visitor in 1987:

"Every spring Djenné's mosque is replastered. This is a festival at once awesome, messy, meticulous, and fun. For weeks beforehand mud is cured. Low vats of the sticky mixture are periodically churned by barefoot boys. The night before the plastering, moonlit streets echo with chants, switch-pitch drums, and lilting flutes. A high whistle blows three short beats. On the fourth, perfectly cued, a hundred voices roar, and the throng sets off on a massive mud-fetch. By dawn the actual replastering has been underway for some time. Crowds of young women, heads erect under the burden of buckets brimming with water, approach the mosque. Other teams, bringing mud, charge shouting through the huge main square and swarm across the mosque's terrace. Mixing work and play, young boys dash everywhere, some caked with mud from head to toe."

This festival, called the crepissage, is under threat, however. The guild of masons is finding it harder and harder to enlist the help of young people for the mud plastering festival. Many young boys prefer to make money as tourist guides or are leaving Djenne’ for the excitement of Bamako, Mali’s burgeoning capital city. In 1988, the old Town of Djenné and its Great Mosque were named a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Market day at the Djenne mosque (Enlarge)

Martin Gray is a cultural anthropologist, writer and photographer specializing in the study of pilgrimage traditions and sacred sites around the world. During a 40 year period he has visited more than 2000 pilgrimage places in 165 countries. The World Pilgrimage Guide at sacredsites.com is the most comprehensive source of information on this subject.

Martin Gray is a cultural anthropologist, writer and photographer specializing in the study of pilgrimage traditions and sacred sites around the world. During a 40 year period he has visited more than 2000 pilgrimage places in 165 countries. The World Pilgrimage Guide at sacredsites.com is the most comprehensive source of information on this subject.